Coping with climate emotions.

How to deal with climate emotions in a sustainable and helpful way. Looking at some new research and lessons from our own work.

Welcome back to Climate Psyched, the newsletter where we write about all things related to climate psychology and how to cope with living in the age of ongoing parallel crises.

One thing we find in our own work as climate psychologists, is that there’s never quite enough time to keep up with all exciting research articles that are published. And in a somewhat ironic way that frustration has been growing in recent years due to more and more research being done in the field of climate psychology, not the least on climate emotions. It’s quite a pleasant frustration to have.

In the last few weeks we have, luckily, been able to dig in to a few recent papers on climate emotions, which we’ll explore deeper and comment on in this edition: Finnish scientist Pahnu Pikkala’s latest article proposing a model for eco-emotions (newsletter Gen Dread had an insightful interview with him about it recently), and Julia Mosquera and Kirsti Jylhä’s prize winning article on normativity of climate emotions.

Let’s dive in!

Situation:

At no surprise to anyone reading Climate Psyched, the climate crisis is a crisis that triggers emotions. Rightly so. The growing presence of climate emotions, however valid these emotions are, requires helpful tools to help us deal.

So how can we approach our climate emotions, and how do we cope with them in a way that’s helpful?

Explanation:

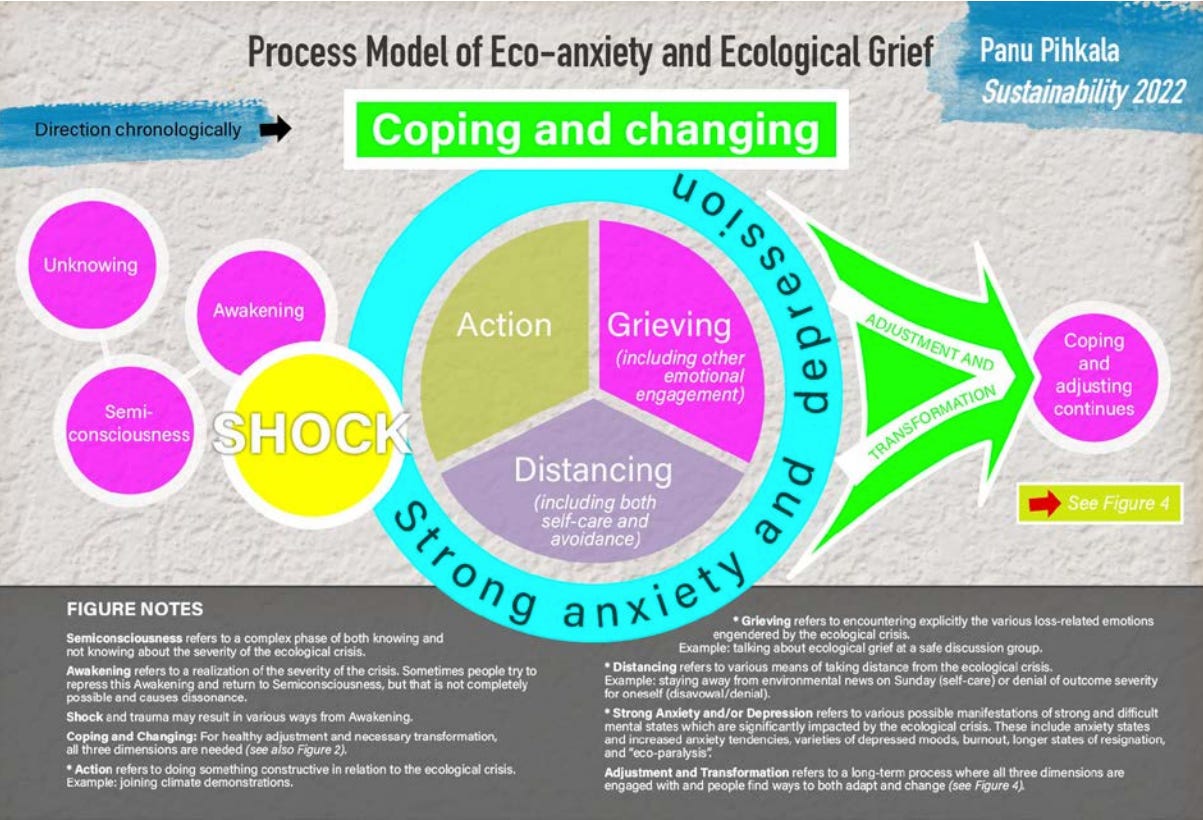

In his article, Pihkala gives an overview over current research on eco-anxiety, eco-grief and eco-distress. He also provides an analysis of what a coping model for climate anxiety might look like, based on a long narrative analysis of existing research and popular science literature.

In plain language: based on a lot of previous books and research on eco-emotions, what could a helpful coping model look like?

The model Pihkala draws up contains three parts: distancing, grieving and acting, all of which are distinct but partly overlapping. According to the model, all three parts are needed. Focusing too much on one part and neglecting another can cause problems. For example if we’re constantly taking action and never allowing space for grieving.

Source: Panu Pihkala

Pihkala stresses that the experience of climate anxiety often fluctuates between different emotional states and between different degrees of intensity of emotions experienced. This means that a climate coping model benefits from being more dynamic than linear, i.e. people do not always follow a straight line/evolution in the experience of climate anxiety, but rather oscillate back and forth between different states. This relates well to the experiences many people with climate emotions are having; feeling their feelings in waves, shifting between different states and moods.

Let’s look a little closer at the three dimensions of the model:

The Action dimension refers to all types of action, ranging from consumer behaviors to political engagement or participation in activism. Pihkala doesn’t further distinguish whether different types of action serve different functions for us, or whether different outcomes of our actions affect our emotions differently. This isn’t entirely in line with previous research, or with general psychological practice.

In the work we do as climate psychologists, we do make a difference between individual action (alone engagement) and collective action (together engagement), not only because collective action often has a better possibility of leading to a higher impact, but also because acting collectively can offer social support in a way that acting alone simply cannot.

Since climate action always takes place in the context of climate change (i.e. we have little time to make massive changes), the consequences of our actions will depend on what and how long an impact they’ll have. (We’ve developed a tool to analyze this better, called the Impact Arrow, that you can read about here). This matters for several reasons, not the least since our emotional state and ability to cope in many ways is related to whether we feel that what we do is making a difference, and whether we feel supported and aren’t alone as we’re taking action.

But there’s another distinction to be made: We would argue that it matters both WHAT action someone’s taking, and WHAT MOTIVATES that action.

There are (in general) two directions in which our emotions can motivate our actions: moving away from something we want to avoid, or towards something we want to come closer.

We might feel worried about the climate crisis, and feel that worry easing if we share a climate post on facebook. In this example, our action (sharing a post) made us move away from the unpleasant emotion (worry), but it probably didn’t lead to any significant change or make us feel supported. Compare this to feeling worried and instead deciding to join a local protest, standing amongst others fighting for the same thing we are. In this case our action (joining the local protest) hopefully made us move a little more towards meaningfulness (fighting for the climate) and give a feeling of support (being around others fighting for the same thing). We also probably needed to overcome (rather than avoid) some uncomfortableness along the way.

It’s natural to want to avoid unpleasant things, but if we structure our lives or our climate actions mainly around doing things in order to avoid our unpleasant emotions, those actions won’t, in the long run, be a sustainable way of coping.

For actions to be sustainable for the planet we need to look at the outcome of the actions, but for actions to be sustainable for our own well-being we need to move towards things that are meaningful and bring pleasant emotions.

The Grieving dimension in Pihkala’s model relates to managing one's emotions and making space for grief. This dimension includes both the management of grief specifically, but also of other emotions. The Distancing dimension includes that which creates distance and provides space to rest from the climate crisis. Being in this dimension requires some balancing since too much distancing can be maladaptive and trigger cognitive dissonance.

In the work we do, educating about climate emotions and supporting people dealing with climate emotions, we usually include both these in an overarching dimension called Emotion Regulation.

Emotion regulation includes all strategies that we use to regulate our emotions, i.e. to adjust the temperature on our “emotion thermometer”, so that our emotions no longer overwhelm or hinder us from doing the things that are important to us. Both Distancing and Grieving fit into the realm of this, but emotion regulation also opens up for a wider range of strategies that are all aimed at making our feelings more manageable. Whilst emotion regulation in itself isn’t aimed towards dealing with the ecological crisis, it is often a necessary step to enable us to then take action.

Part of this includes the process of building up one’s tolerance for uncertainty and uncomfortable emotions. Learning the skill of being with oneself even when not feeling good, when it’s hurting and when you don’t know what’s going to happen. Sitting with yourself without judgment, trusting that whatever feelings happen to be present at any given moment eventually will pass. This is a skill that can only be learnt by practicing and by being present with whatever feelings are felt.

Our emotions never exist isolated from our social and societal context, which means that the possibilities of coping with climate emotions also will be affected by what (and who) we have around us.

Mosquera and Jylhä explore this in their article, and illustrate how a person with climate emotions often needs to deal with affective dilemmas about what’s “correct” and not to feel. These dilemmas are influenced by the public debate and social norms around climate emotions. Is it okay to feel happy on a hot summer day? Is it okay to enjoy life whilst still being involved in the climate issue? They also bring up the danger of not allowing people who’ve been subject to oppression to feel what they’re actually feeling, leading to so-called secondary injustices. The discussion on what social norms surround different emotions are important since the efforts to get people to be less emotional, or not feel (whatever emotion isn’t socially acceptable) usually leads people to both experiencing their emotions more intensely and judging themselves for having those emotions.

Emotion regulation isn’t about not being allowed to feel what you feel, but finding ways of taking care of whatever you happen to be feeling and channeling that into whatever serves you well, whether that be taking action or taking a nap. Whether it be grieving or distancing.

As Mosquera and Jylhä discuss in their paper: Feelings are sources of information about our internal and external environment. Learning to listen to that information is essential in coping with our climate emotions.

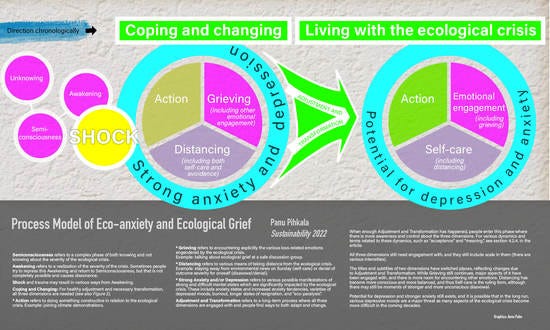

If one can follow some chronological progression, Pihkala reasons that people gradually undergo a process of adaptation and change that makes their coping skills more well-adapted. Pihkala visualizes a potential later stage where the headings and subheadings of two of the circles are renamed: Grieving is replaced by "Emotional engagement" and Distancing is replaced by "Self-care" to more clearly reflect that in a more well-adjusted state, grieving or distancing do not take up as much space. Regulating our emotions is a skill that we can get better at as we practice.

Source: Panu Pihkala

ACTION:

There is no right way to feel about the climate crisis, but there are certainly better or worse ways of acting (or not acting). Preferably find ways of acting that both contribute to your own coping of your emotions, and to our collective coping of the climate crisis (in other words: actions that contribute to mitigation, adaptation and healing)

Nurture the acceptance of your own emotions. It is okay to feel however you happen to feel, and it’s okay for those feelings to change over time. Feelings are neither good nor bad, they just are. If we give them space and acceptance they will interfere less with our possibilities of taking action. And, as it seems, if we nurture a wider acceptance of the range of emotions that exist and that sometimes show up in unexpected ways, we might also nurture more possibilities of taking action. How we cope with our emotions affects what possibilities we have to act.

Identify why you’re doing something, and what consequences it will lead to. If keeping up with all climate news is motivated by fear or guilt of not being involved enough in the issue, and leads to the long term consequence of becoming more and more stressed, then there are probably more meaningful ways of spending your resources.

Do ask yourself: “How can I best be of service, and what do I need to be able to be of service for many years to come?” Taking care of ourselves in a way that enables us to be of service is one of the most responsible things we can do. Knowing our limits and tending to our needs are things not only beneficial for ourselves, but also for the groups and issues we may be engaged in. Taking on too much out of guilt for not doing enough isn’t helpful for anyone.Taking care of ourselves and our emotions in a way that allows us to engage in a long term sustainable way is one of the most responsible things we can do. Practice to listen to your needs and limits, and practice saying no when needed.

It’s thrilling that the research on eco and climate emotions is progressing with such grace (and speed!), and that the practical work more and more of us do out in the world is reflected in this. Dealing with the climate crisis certainly entails a considerable amount of learning as we go along, and not the least learning from each other as we all take steps forward.

Thank you for reading, as always, we love to hear your thoughts and reflections about the topics we bring up. Feel free to share this post with whomever you think might find it useful or helpful!

Until next time, take care of yourselves.