Finding comfort in the movement action plan

On the Movement Action Plan (MAP) and how to view our current struggles in a wider perspective.

Welcome back to Climate Psyched, the newsletter where we explore all things psychological, behavioral and emotional related to the climate and ecosystem crises.

Lately it’s been feeling like there’s so much bad things happening all over the place that it’s hard to keep up. It feels like everything is moving in the wrong direction; increased repression, deconstructed democracy, wars that just keep raging on.

When met with obstruction and resistance it’s easy to become disheartened, and feel like you might as well give up. When overwhelmed with feelings of disbelief and disappointment, people have a tendency to zoom in on a shorter time span which can increase these feelings of despair. So for this month’s post I’m trying to find some comfort in zooming out and looking at the wider picture, with the help of the Movement Action Plan.

Situation

Currently, there are a lot of examples of how things seem to be going in the wrong direction. Repression of climate activists is increasing in several countries across the globe, including the UK and Australia, making it harder to stand up for climate justice. A recent report shows that this is in fact a global trend. Parallel to this far-right forces are gaining traction, obstructing climate work and increasingly posing a threat to democratic institutions and values. Does all of this mean that we’re losing?

Explanation

Not necessarily. Back in the 1980’s, activist-educator Bill Moyer developed the Movement Action Plan (MAP). MAP is a theory that explains how social movements make progress, and how encountered obstacles along the way actually might be a sign of progress. MAP includes eight stages through which social movements usually progress over time (from a few years up to several decades). As the acronym suggests, MAP actually does provide a sort of map for organizers and activists to help guide their actions, and keep motivation over time.

Moyer describes eight stages through which social movements normally progress over a period of years and decades. For each state, MAP describes the role of the public, power-holders, and the movement.

Stage One: Normal Times

This first stage is characterized as politically quiet times, where critical issues that violate society’s common values (e.g. democracy, security, justice) aren’t on the political agenda. Those in power aim at being perceived as upholding societal values, but are in practice violating them - which is partly possible due to a large unawareness in the public perception. At the end of this stage new grassroots activists realize that the critical issue exists but that none of the established power structures are willing to solve it, and that the established channels in society are unapt to solving the issue.

Stage Two: Prove the Failure of Institutions

This is the stage where the opposition needs to prove that there is a critical issue that is upheld by current powerholders. This entails getting enough people aware about how governmental policies are violating widely held societal beliefs, and to gather facts and proof that this is in fact happening. The growing movement is using established ways for democratic influence, while the people in power are (quite easily) pushing back the opposition without having to feel too threatened. The majority of the public keep supporting status quo, but the opposition is growing even if the issue isn’t yet on the political or medial agenda. Eventually activists in the movement realize that they need more political action and democratic influence to genuinely tackle the identified issue.

Stage Three: Ripening Conditions

For a social movement to take off and thrive, there needs to be certain conditions, e.g. that a large enough group is affected by the issue or are allies. In this stage the discontent with status quo is growing, as are the expectations that something else is possible. Grassroots are forming and organizing smaller demonstrations, visionaries are shedding light on the issue and existing groups are preparing to offer support and people to the new movement. Powerholders are still quite unconcerned, and not yet substantially challenged, still controlling established institutions and having the public’s support. Awareness of the issue amongst the people is however growing, and an opposition is forming, with people getting more and more frustrated over the issue and how powerholders are violating common values and making things worse.

Stage Four: Social Movement Take-Off

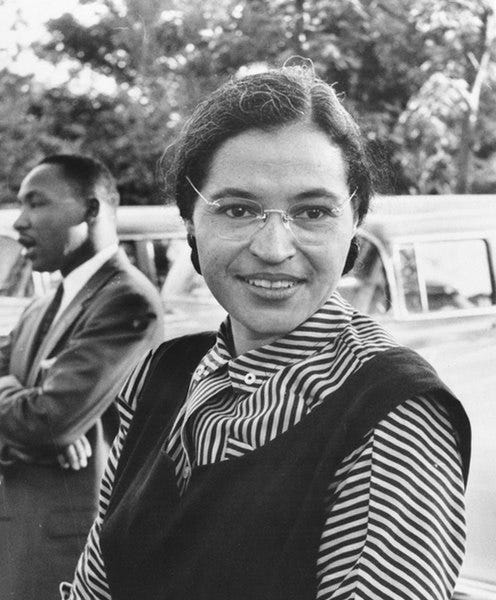

A stage that can happen quickly, seemingly overnight, as a social issue becomes the talk of the town and media. Often triggered by a shocking incident that’s followed by an action campaign with large rallies and civil disobedience. These campaigns are often repeated in local settings across the country. Historical trigger events preceding social movement take-off are for example the arrest of Rosa Parks. The trigger event displays to the public how those in power intentionally cause the problem, which makes the public demand answers from the powerholders, and open up to join in demonstrations for the first time. The organization of demonstrations and protests are at this stage often spontaneous and loosely organized, not seldom driven by more radical activists and rebels. Powerholders are often surprised and a unprepared for this stage, and as the public become more aware and educated on the issue a stronger opposition against the current politics is formed. This phase usually lasts between 6 months and two years. More and more people join in, take on less radical roles and begin to focus on local organisation and education.

Stage Five: Identify Crisis of Powerlessness

Even though the movement has achieved the goals in Stage 4, the high expectations of seeing change leads to despair, and a feeling of failure. The movement might be portrayed as irrelevant or even dead. The powerholders seem too powerful, and activists and citizens start to feel too powerless to truly believe that change is possible. As the movement starts transforming, many activists can also fall into believing that the portrayal of them is accurate and that the movement is - in fact- irrelevant. Fewer keep up motivation, attend protests and meetings. It can feel hopeless that more things aren’t happening even though the public opinion is supporting the goals of the movement, and the movement has managed to put their core issues on the political agenda. This is a phase of miscrediting the movement, of increased repression and of trying to associate activists with negative stereotypes. Radical activists are often portrayed as representatives for the wider movement. This also makes it harder for the public to know what or who to believe, people’s status quo bias kicks in and many are afraid of what change would entail - parallel to seeing that the current status quo is unsustainable. This stage can happen simultaneously as stage 6. Once the movement transforms and shifts some of its used methods, they can fully enter into the next stage.

Stage Six: Majority Public Support

In this stage the movement shifts from spontaneous activity and protest to a more long-term, systematic struggle that becomes popular enough to include more grassroot activists. Here’s where the changemakers start playing a larger role as the movement wins more and more of the public’s support. The public starts questioning the current politics and are considering alternatives. It’s not necessarily a swift process, but rather a slow and tedious one, where the movement works towards weakening the social, political and economic support of the current powerholders, to create a new social and political consensus. In this stage, powerholders usually defend current policies, but adapt their rhetorics to gain support as well as use financial power to stop funding activities and groups that question their policies. The surveillance and discrediting of the movement continues. Support against powerholders policies can increase by large numbers within a few years, but there’s still no consensus on what the preferred alternatives are. Eventually politicians and powerholders join in with the voices who are asking and acting for change.

Stage Seven: Success

When there’s a large enough opposition that push for political alternatives and system change, a new social consensus begins to take place, and those in power become more isolated and hindered, which can lead to more and more people in power switching sides. People now want change, more than they fear the alternatives to the current status quo. This shows by a willingness to vote, demonstrate and support new policies. The movement reaches a big goal, but other goals persist. It’s still a stage of continuous struggle, although more of a downstream struggle, as the movement keeps growing and gets support from more and more mainstream actors and previously passive citizens.

Change in this stage can come about in more visible and dramatic ways, in a more quiet showdown or by attrition, where those in power stubbornly persist but step by step are worn down.

Stage Eight: Continuing the Struggle

The world keeps turning, and for good and bad, there’s never any end point (note to anyone who thought that the rights our older generation fought for wouldn’t require any defending once they were established). The struggle continues, and new solutions can be implemented.

(References for this text come from here and here, and from a presentation by the Swedish alliance for a just climate transition ARK.)

Action

Moyer outlined MAP in the 1980’s, when many things looked different in the world (for one, people didn’t have access to the internet!), and it’s not a given that these stages accurately describe the development of social movements today. But, it’s a tool that can help us navigate our actions, emotions and way of organizing. So keeping that in mind, here are a few things we can do to cope with things right now:

Practice zooming out and looking at a wider time frame.

Practice separating your immediate feeling of hopelessness, or despair, from the long-term outcome of that which you’re fighting for.

But also allow yourself to despair, to feel hopelessness, to grieve, to feel whatever you might be feeling at the moment. Heavy emotions can in all their heaviness offer much needed space to pause, decompress and reorient. Remember that all emotional states are impermanent.

Actively search out people, organizations and initiatives that in various ways are contributing to keeping the fabric of society together. Those who offer their time and care to help others and who keep resisting anti democratic forces. They are always important, but in darker times they can be an essential source of solace.

If you’re involved in the climate movement, stick with it! See if you together with others can identify which stage you’re currently in, and what you can do to keep motivation up, and prepare for your next steps. You are as needed now as ever.

As always, there’s much more to say on this topic, for example what different roles people can take on in bringing about change and how they relate to these different stages. I’ll expand on this in the upcoming mid-month post for paid subscribers.

Upgrade to paid subscription

For those who want to and are in a position to financially support this work there is now the option of becoming a paid subscriber to Climate Psyched, . Writing Climate Psyched is a labor of love and one that truly feels important, but it is nonetheless labor that takes a substantial amount of time and effort. If you do become a paid subscriber you will not only make me feel incredibly honored, you will also receive an extra post per month.

These monthly posts will still be available free for everyone - it feels important to not exclude those who don’t have the financial space, as well as acknowledging that support for someone’s work can come in many different forms.