How do we get the rich to change behavior?

The latest research on how to increase pro-environmental behaviors, and the ever ongoing debate on individual vs. systemic change.

Welcome back to a new edition of Climate Psyched, the newsletter where we explore and dig into all things related to climate psychology, behavior change and living in this time of climate and other crises.

It’s that time of the year again, when ppm levels spike and are higher this year (again) than last year. Up in Sweden it’s on the contrary becoming greener and you can almost start to feel the oxygen produced by trees and plants bursting with new life. A reminder of the dissonance we can feel when standing in a thriving spring garden, yet intellectually knowing that the levels of carbon dioxide are dangerously high.

We’re not gonna talk about ppm levels today, but we are gonna talk about a key factor in stopping ppm levels from rising: getting high emitters to change behavior. And of course go through some recent research.

Situation

A few weeks back a brand new secondary order meta-analysis, analyzing hundreds of studies with different interventions aimed at increasing pro-environmental behaviors, was published.

There’s also been two pre-prints announced (Kukowski et al., and Hagmann et al.) by two research groups, dealing with the questions of whether we should focus on individual or systemic change - or both. This sparked a bit of a discussion between researchers from the two groups, that you can read here and here. It’s an interesting discussion and one that will surely be continued for as long as we’re trying to fix this massive problem that is the continuous burning of fossil fuels due to extravagant lifestyles.

But, in light of the newly published meta-analysis, I find that there’s something we’re oftentimes miss in the ever ongoing individual vs. systemic change debate: considering that we have very little time to massively reduce and eventually phase out all emissions, HOW do we in the fastest and most efficient way get the rich high-emitters to change their behaviors?

Explanation

Let’s start with the new meta-analysis, by Bergquist et al. It looked at 430 primary studies that only included voluntary interventions (i.e. no regulations, taxes, laws or other forced policies) and only interventions with the intention of facilitating pro-environmental behaviors. The researchers found a varied set of interventions: Appealing to people, making a voluntary commitment, educating people, giving people feedback on their behavior, using financial incentives or social comparison. The pro-environmental behaviors explored in the studies were grouped in the following categories: conservation, consumption, littering, recycling, and transportation behavior.

The researchers found that the most effective types of interventions (with the largest effect sizes) were social comparison and financial incentives, whereas the least effective interventions were feedback and education. This isn’t really surprising, as we know from much previous research on behavior change that information and educating people generally is insufficient to enable actual changes.

But one of the most important findings in the paper - especially regarding the acuteness with which we need to phase out emissions - was that even the most effective interventions were quite ineffective in changing high impact behaviors, such as transportation behaviors. They work well for getting people to do the small stuff, like stop littering, recycling and conserving water, but not for the larger stuff.

This brings us back to the high emitters (primarily the richest 10% globally). Now, it could be that the richer you are the more you litter and that this littering produces quite a bit of emissions, but it’s safe to say that the large part of high emitters’ emissions comes from fossil intensive activities like travelling by airplane, driving large cars and owning large energy demanding homes. These are the behaviors that need to change and that need to be targeted.

And according to this new research, when it comes to high impact behaviors, voluntary interventions don’t seem to do the trick. We simply cannot appeal to high emitters goodwill to get them to change, and chances are that social comparison in this group still is associated with comparing oneself to other high emitters where the social norm is to live a fossil intensive lifestyle.

This brings us back to something we’ve written about previously: high emitters have a higher emission reduction potential and a greater role model potential (not to mention a larger responsibility). But it seems that in order to get high emitters to make actual changes we need to move away from voluntary measures and focus more on systemic changes. The new preprint (a paper that hasn’t yet been peer reviewed) from Hagmann et al., shows that a focus on individual behavior seems to make people less prone to hold organizational actors responsible for solving problems such as climate change. This is in line with previous research (also by Hagmann and colleagues) showing that the presence of a nudging intervention can reduce support for binding but more efficient policies like a carbon tax. People seem to be unable to focus on everything at once, so we do best in focusing on what seems to be most efficient straight away.

Take transportation behavior for example. A study by Kuss & Nicholas (summarized by Nicholas in her newsletter We Can Fix It) analyzing measures to reduce city traffic, showed that the three most effective measures were: Congestion charge, parking & traffic control, and limited traffic zones. All involuntary measures (that however combined carrots and sticks motivators), and all measures that require political decisions and infrastructural changes. This follows an important principle when it comes to behavior change: When we change the context and preconditions where people’s behaviors take place, their behaviors are more likely to change. In other words: if you want to reduce car traffic it’s better to impose a congestion charge and remove parking spaces than try and motivate people to start biking in an already congested city.

How do these types of measures relate to individuals and the always important question of “What can I do?”

Well, if we are to enable systemic changes we need to engage in indirect mitigation behaviors; behaviors that indirectly aims at reducing emissions. For example protesting, contacting politicians, talking to your boss about your work travel policy, organizing to start a campaign to ban private jets. Usually indirect mitigation behaviors are done collectively, and they’re never isolated actions, but rather a collective set of behaviors that aim to influence decisions, laws, regulations and policies. (We explain about direct and indirect mitigation behaviors more in detail here)

In other words: rather than appealing to high emitters to stop flying and ditching their large car, start working to push for laws banning private jets and large SUVs.

And in the name of not saying either or: if you’re a high emitter who’s motivated to change, please do! We become more trustworthy messengers when we ourselves have made the changes we’re pushing for, and showing the way can help motivate others around you. Just don’t forget your potential for indirect mitigation actions!

Action

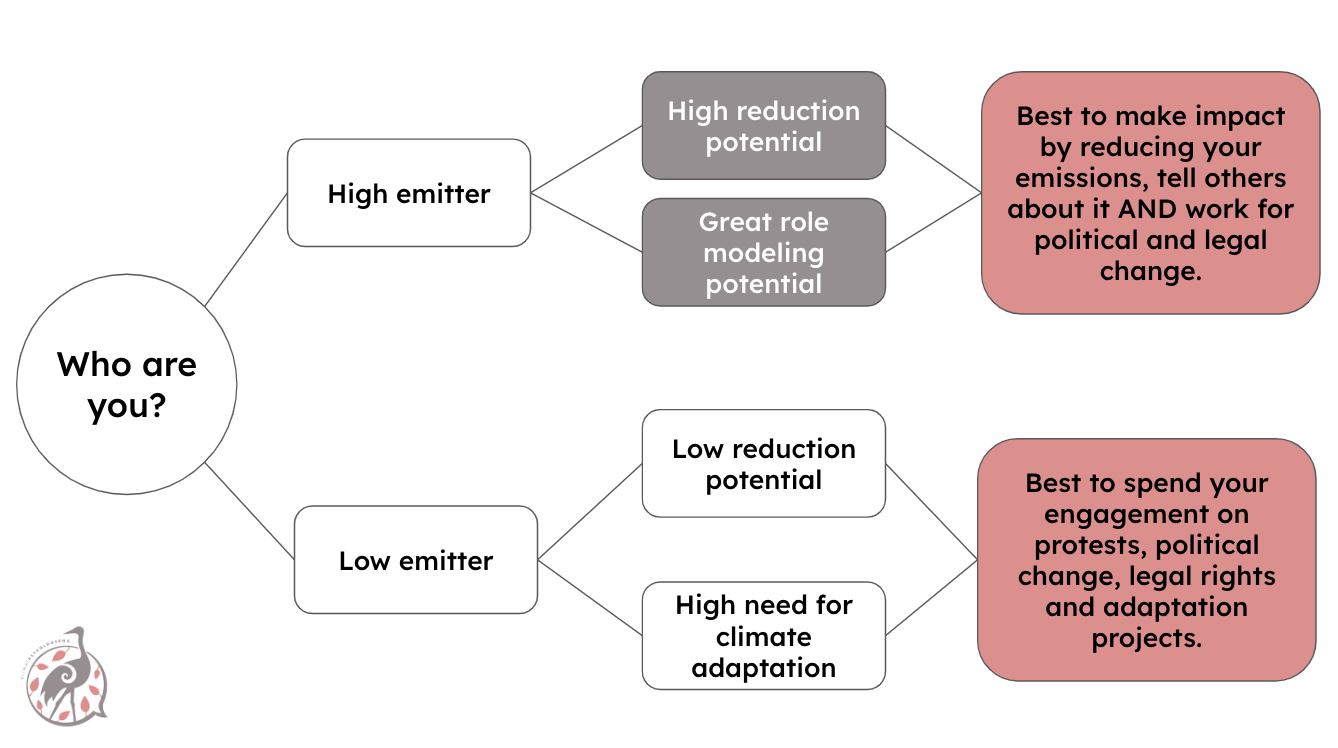

We made a (somewhat simplified) model to help navigate who has the potential to do what in terms of what behaviors we engage in. We think it’s a good start and reminder that we have the potential of doing more than reducing our own direct emissions.

In the current situation of needing to make changes throughout every dimension of society we can’t really afford to say we’ll do either A or B, but considering how little time we have to make these massive changes we do need to be strategic when it comes to what interventions aimed at behavioral change we put our time, money and efforts into. In other words aiming for high impact and long term changes.

We hope that the discussion on what types of interventions and methods are most efficient for bringing about the needed behavior change will continue and that we continuously learn more about how to best getting high emitters to reduce their emissions.