IPCC and why information isn't enough

Welcome to the first edition of Climate Psyched! We're talking about the new IPCC report finally turning to social sciences and why information just isn't enough.

Warmly welcome to this (first) edition of Climate Psyched! Our aim in this newsletter is to look deeper into how we humans (more or less successfully) handle the climate crisis. In each newsletter we’ll highlight a current event, explain it from a climate psychological angle and channel it into concrete action. We’ll share interesting research articles, helpful resources and give you snippets from our book “Climate psychology” (currently available in Swedish, we’re working on an updated and translated English version)

WHO WE ARE

Before we dive in, you might be wondering who’s behind this publication?

Writing Climate Psyched are four Swedish licensed psychologists - Frida, Kali, Kata & Paula - who for years have been specializing on the psychological, behavioral and emotional aspects of the climate and its relatable crises. Apart from being psychologists we have backgrounds in fields like climate activism, human ecology, permaculture, research and organizational development. We do a wide range of stuff in our everyday climate psychology jobs, such as developing methods and materials for youth struggling with painful climate emotions, lecturing about why more isn’t happening despite many people’s efforts, hosting workshops on how to create large-scale sustainable change, writing op eds to encourage brave political action, talking to the media as much as we have time for, and being available as resources to help building resilience amongst climate activists. We’ve published a book that’s already sold thousands of copies, generated numerous book circles and is being used in climate & sustainability work in several municipalities and organizations.

Moving on to the main event of this letter: The recently published IPCC report from Working Group III on Mitigation of Climate Change, that was released on April 5th. More specifically the fact that IPCC for the first time has included a chapter that concerns behavioral change and the potential for mitigation through social aspects. The report states that behavioral and cultural changes have been a “substantial overlooked strategy”, often left out of transition pathways and scenarios. While the report yet again is quite a horrifying read (Carbon Brief has made an excellent summary, as has Zentouro on YT), it is good news that social sciences and behavioral aspects are beginning to make its way into the IPCC reports. Why? We’ll explain below.

SITUATION:

We assume that anyone reading this publication is aware that 1. We’re in the midst of a massive climate crisis that requires fast, enormous, large-scale action that needs to happen within the next decade, and 2. For years we have been aware of climate change, its causes (somewhat simplified: the extraction and burning of fossil fuels) and potential solutions (also somewhat simplified: stopping the extraction and burning of fossil fuels) - yet we’ve seen emission continue to increase year after year. We’re dealing with a situation where the information we have at hand isn’t matching our efforts to solve the problem.

There’s a multitude of factors and explanations for this, but for the sake of creating some common ground for everyone reading this, let’s start with a very fundamental fact: information is in itself not enough to create behavioral change.

The report states that motivation to change energy consumption behavior by individuals and households is generally low worldwide. The report also says individual behavioral change is insufficient for climate change mitigation unless embedded in structural and cultural change. Different factors influence individual motivation and capacity for change in different demographics and geographies. These factors go beyond traditional socio-demographic and economic predictors and include psychological variables such as awareness, perceived risk, subjective and social norms, values, and perceived behavioral control.

One conclusion is that that behavioral nudges promote easy behavior change, e.g., “improve” actions such as making investments in energy efficiency, but fail to motivate harder lifestyle changes. The IPCC now fully understands that we need more methods than information if we’re gonna make the unprecedented changes that lie ahead of us.

EXPLANATION:

Who’s ever heard of such a thing as human beings knowing that something is bad for us, but still continuing to do it?! Unless you belong to a rare subspecies of homo sapiens that never errs, always goes to bed on time, never drinks that extra glass of wine and wake up with a headache the next day, and always manages to get out of the couch and off to the gym, you’re probably like most of us: we do a lot of stuff even though we have the knowledge about it not being good for us.

Over the years we’ve talked to climate scientists who’ve frustratingly stated that they for a long time thought that it would be sufficient to merely communicate the science. It was unthinkable that anyone could hear the information about climate change and then fail to take action. Dealing with climate change, a lot of attention has been given to the natural sciences and the ever emerging research on how the climate is changing due to anthropogenic emissions. And righteously so - knowledge and information are in one way absolutely essential. How else are we to know what’s going on, and what to do? For many years (and still in many ways!) climate communication and the environmental movements have used information spreading as a foundational method to spark change.

This builds on the assumption that behavioral change works like this:

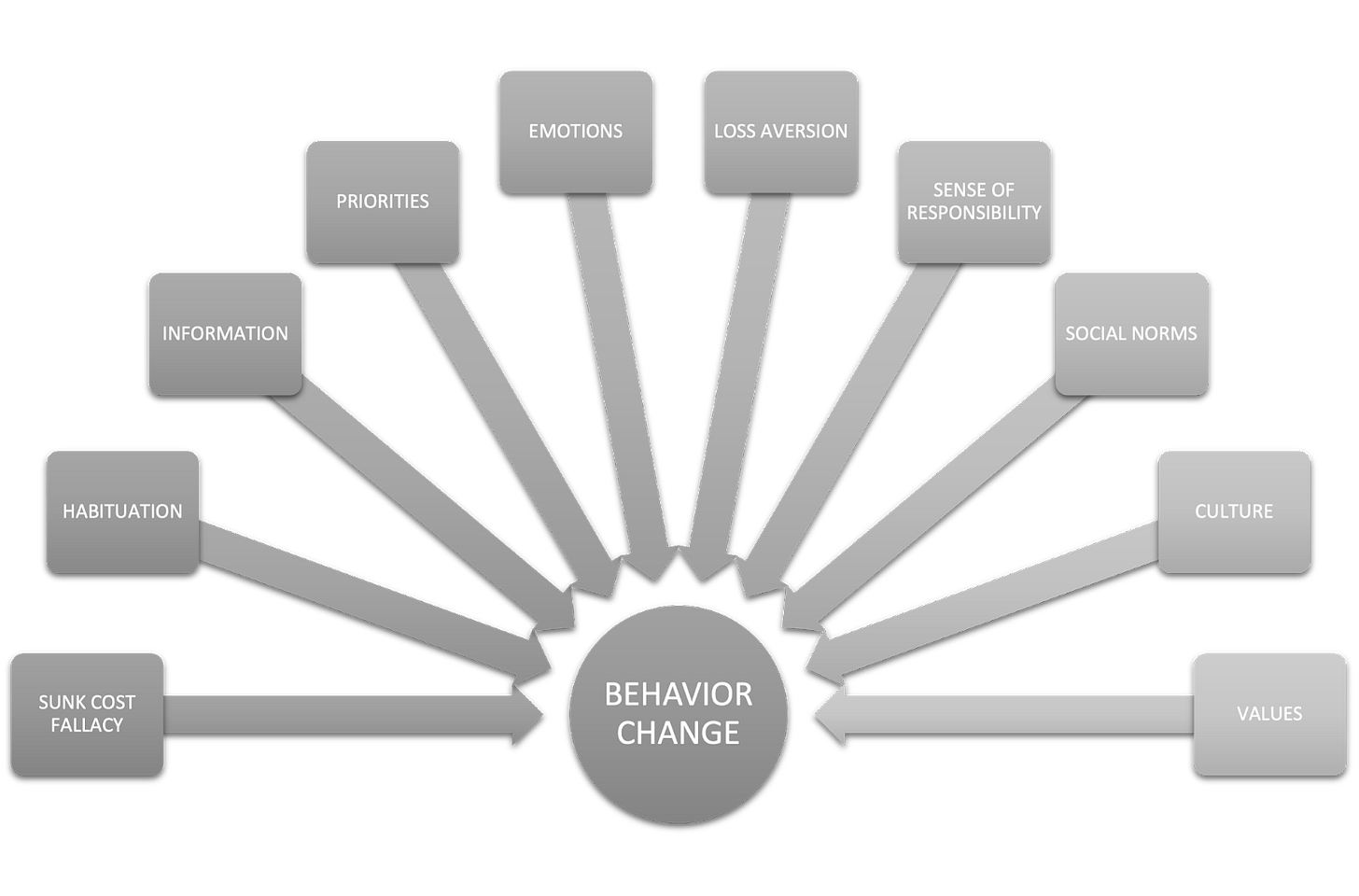

Oh, what a wonderful world it would be if this had been the case! Unfortunately for us, and for climate change, what shapes our behavior is a little more complex than that. It looks more like this:

There’s an abundance of factors that influence the way we act (even more than those above!). They do however have one thing in common: we’re an emotional, social and contextual species. Information may inform us of what would have been the rational thing to do in all situations, but at the end of the day we’re usually more prone to keep doing what we’re used to doing.

To make things trickier, communication around climate change has for decades intentionally been confused by very active and systematic lobbying efforts, with the intention of sowing doubt and making climate change seem less acute than it actually is. There’s much to be said about this (if you want to quickly learn more, listen to the excellent podcast Drilled). You can be sure that we’ll return to this subject later on. But for now we can agree that information about global, super wicked problems, isn’t just one single thing that comes from one single reliable source, and isn’t perceived the same way by everyone and definitely not with the same openness for change.

ACTION:

Climate interventions aiming at changing people’s behaviors demand more methods than the spread of information! But even when spreading information there are a few actions that are more important to take.

We’re more open to receiving information from someone we trust. As climate engaged people, we will not be the best messenger for everyone, especially without tailoring the information to fit the person or group we’re addressing. If we do wish to get more people on board the climate transition we need to shift perspectives from what we find most important, and try to find out what they find important - and then talk about how that’s related to the climate crisis (the good and bad thing is that climate crisis concerns pretty much everything).

That way you’re more likely to 1. Create engagement, 2. Actually get the information about the climate across. A little less talking, a little more listening, but in the end a higher chance of actually having the information facilitate change.

Remember that information is only one of many factors that will contribute to change and not where we should direct most of our efforts. It’s often more efficient to work with things such as changing norms, regulations and the surrounding context. All of these things can attain higher effects if we do them collectively. More about that in upcoming editions of Climate Psyched.

Want to read more about how information campaigns are an ineffective way to increase behavior change - here’s a small snippet from our book talking about the information trap:

Information is only a small part

The assumption that information leads to change has been reflected in many interventions in areas such as health and community development. Over the years, many millions of dollars have been spent on large information campaigns, with mediocre results. In the early 2000s, for example, an information campaign was carried out in Sweden to get more people to have safe sex. Opposite to the goal of the campaign in 2004 the number of reported cases of chlamydia increased from the first to the second half of the year by 46 percent among teenage girls and 69 percent among teenage boys..

Researchers from Örebro University, Karlstad University and Norwegian Social Research decided to take a closer look at the effectiveness of large public awareness campaigns. They argue that the vast funds spent by public authorities in Sweden and other countries on various information and awareness campaigns do not have any long-term effects. They investigated whether a Norwegian information campaign on pension savings had long-term effects in terms of increased knowledge and increased pension saving. The results showed that after only four months, most people had forgotten the content of the campaign and almost none had changed their pension savings.

The pension study is just one in a series that strongly question the usefulness of public information campaigns. But information campaigns continue to be the most common way of communicating to the population when trying to increase or decrease specific behaviors. It seems that we humans love to give information, but are rather uninterested in receiving it. But really it's neither a matter of disinterest nor irrationality. The reason is that there are so many other factors that also influence our behavior. Let's examine what makes the information reach the recipient the way we hope it will. (If it does at all.)

The messenger matters

Imagine a politician you really don't like making a new statement about something you actually agree with. But there's still something unappealing about it; the message is coming from someone you usually think the opposite of, someone you don't identify with at all and who you dislike. Suddenly you start to doubt the message. Can it really make sense if it comes from this person?

We always filter and assess information based on the messenger. Whoever is behind a message, or whoever we think is behind a message, influences how we perceive the message itself.

If we have a high level of trust in the person giving us the information, we tend to question less and take in more of the content. In countries such as Sweden, authorities, politicians and public service media, are often interpreted as credible and objective. Unless you are a person with low trust in government agencies and politics, then you are likely to be more skeptical about what drops into your letterbox from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency or the Swedish Civil Protection Agency. If your identification is on the left flank of the political scale, you are likely to be skeptical of most things a Sweden Democrat says, even if there are occasional proposals that you actually agree with. Similarly, a diehard conservative is likely to be skeptical of most things a left-wing politician says. We find it easier to accept information that comes from someone we trust and like. The messenger plays a big role, sometimes greater than the message itself.

We hear what we want to hear

We also find it easier to take in information that largely confirms what we already know and believe. It's another cognitive bias called confirmation bias, or more simply, confirmation of the worldview. Perhaps you've noticed that there's suddenly a lot of writing and talking about climate change? It's not just because the number of articles on climate change has actually increased in the media, but also because you have an interest in the subject. As we are confronted with an enormous amount of information in different channels every day, our brains help us sort what seems important and interesting - which often means that we accept what already confirms our worldview. Randomly spreading information on sustainability and the climate crisis is therefore most likely to reach the already saved.

Selected references:

To govern the state. The government's governance of its administration. SOU 2007:75. Stockholm: Fritze.

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A. & Whitwell, G. J. (2014). Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention-behavior gap. Journal of Business Research, 67 (1), 2759-2767. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.09.022

Clayton, S. D. & Manning, C. M. (2018). Psychology and climate change: Human perceptions, impacts, and responses. London: Academic Press.

Echegaray, F. & Hansstein, F. V. (2017). Assessing the intention- behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: the case of Brazil. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 180-190.

Klöckner, C. A. & Ofstad, S. P. (2017). Tailored information helps people progress towards reducing their beef consumption. Jour nal of Environmental Psychology, 50, 24-36.

Kollmuss, A. & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro- environ- mental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8, 239-260.

Passer, M. W. & Smith, R. E. (2011). Psychology: The science of mind and behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education

Sheeran, P. & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention-behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10, 503-518. https://doi. org/10.1111/spc3.12265

I too am psyched to follow this newsletter about climate psych. :-)

I applaud the “plain language” tone of the initial post. Thank you for that!

In a tweet in response to Kimberly’s act of kindness alerting me to this newsletter I noted: “The peacock graphic focuses only on individual behavior. To achieve decarbonization & resilience at the necessary scale & pace also requires a focus on the attributes of place: policies, physical environments, products/services.” I hope my comment came across as a helpful suggestion to include higher units of analysis in this conversation—social networks, organizations, communities, the attributes of place—in addition to a focus on individual-level psychology.

Individual behavior is necessary—especially if the behavior is focused on actions that have leverage in producing system change (e.g., advocacy actions aimed at public, institutional and corporate policies)—but not sufficient. I look forward to participating in the conversation about how we can use our insights as social and behavioral scientists to bring about what is necessary and sufficient to achieve decarbonization and resilience at the necessary scale and pace.

I'm psyched for this newsletter! Excited to read more!