Let's talk about flygskam (flight shame)

Do people know that flying is bad for the climate? And do they care?

Welcome back to Climate Psyched! Or if you’ve just made your way here: Welcome! There’s over a thousand of you reading and subscribing to Climate Psyched, which feels like an immense privilege and honor. We’re so happy that so many of you are interested in exploring all things related to psychology, emotions, behavior and the climate (and its related) crises together with us.

The main topic this time is flying and feelings. Flying evokes feelings, not just for those still traveling by air; one of the most common questions my colleagues and I get is how to deal with seeing flight pictures in one’s social media feed. Having taken the step to quit flying and seeing others continue with business as usual triggers a lot.

My personal solution (which probably shouldn’t count as professional advice, but more as a very human this-is-so-hard-to-deal-with) has been to put my friends who gladly post pictures of flight vacations on mute on my instagram. We all need to find our strategies, right?

But let’s unmute the frequent flyers for a bit and dig in!

Situation

The overall emission from aviation is, according to Our World in Data, 1,9% (81% from passenger travel and 19% from freight), but that number doesn’t account for the full climate impact, and as an article in Carbon Brief points out, its true impact is significantly more profound.

Considering that only 11% of the global population travelled by airplane in 2018 (only 2-4% travelled internationally), and that 1% of the world population accounts for 50% of the overall emissions from passenger air travel, it’s fair to say that climate impacts from airplanes is also a question about global justice and of who gets to eat of the remaining carbon budget cake.

If you are a person who travel by airplane, chances are quite big that those plane trips make up the biggest portion of your personal carbon footprint, and staying on the ground might be the one decision with most potential of reducing your personal climate impact.

Back around 2018, there was a lot of talk about the climate impact of air travel in Sweden. A group launched the campaign “I’m staying on the ground” and media started picking up on people’s decision to quit flying. As a country that has an intricate relationship to shame, it’s no wonder that the word flygskam (flight shame) was soon established, started making its way around the globe, and even into the research literature.

But is shame an efficient strategy to get people to quit flying? Do people even know that flying is bad for the climate? And do they care?

Explanation

A study from 2020 looked at the carbon numeracy (i.e. how people perceive the carbon footprints of individual actions) of 965 North Americans. The researchers saw that the study participants underestimated the emissions of air travel. They also saw that people are largely incapable of estimating how the emissions from different actions compare to each other (e.g. how many hamburgers would be the emission equivalent to taking a trans-Atlantic flight). However, a slightly newer study of a Swiss sample found that the study participants accurately perceived air travel as a high impact individual behavior, but did indeed overestimate the potential of low impact behaviors such as switching out light bulbs and switching plastic bags for canvas bags.

In the report International attitudes toward climate change, where attitudes of 20 countries are studied, it becomes clear that knowledge about airplanes’ (relative to cars, trains and buses) high emissions vary vastly between countries, as can be seen in the picture below. While 73% of Germans seem to know this, only 41% of Americans do. And in Indonesia a mere 18% agree with the statement. With this in mind, in terms of lowering one’s own emissions it’s more important that the people who actually travel by airplane themselves have this knowledge, than the vast majority of the global population who’ve never set foot on a plane.

There are very few studies on the connection between people’s emotions and the decision to quit or reduce flying. One attempt to explore people’s reasoning behind the decision to quit flying was made by Swedish researchers in 2021. The qualitative study only included people who had already quit flying. In their analysis they saw emerging themes of fear, wanting to act morally and in line with one’s conscience as reasons for the decision to stay on the ground. Children, role models and having a socially supportive context also played in. Shame was, however rarely mentioned by the study participants.

Now, however interesting it is to explore the reasoning of people who’ve already taken the step, it’s tricky to know whether the reasons people formulate in hindsight are the same as what actually drove them to the decision in the first place. As a clinical psychologist of ten years, I know firsthand through following my clients’ behavior change processes that people often tend to change the narrative around their previous decisions once they become more distant and less affective. Shame is a feeling that even in the safety of the therapy room can be hard to recognize in oneself, and even harder to express. Perhaps because shame, in its essence, makes us want to hide from others.

In the research on social norms, scientists have explored how the influence of social norms is underdetected, i.e. that people say that they are less affected about what seems socially accepted and desired than they actually are. To put it more bluntly: we all want to be perceived as individuals with our own sense of agency and rationality, but it seems we are far more affected by others than we dare to admit.

Shame is a difficult emotion. It’s heavy to bear, and since it’s such a social emotion it’s also one that makes us isolated and lonely. The very impulse when feeling shame is to hide from the world. If you’ve ever looked at a small child being ashamed you’ve noticed how they often place their hands over their faces and look down, as if to say “don’t look at me, let me be!”

Shame is, generally, a potent behavior regulator (i.e. something that makes people regulate/change their behavior). Or rather, the very fear of shame is. People navigate through life by getting cues from others about what’s okay and not okay in various contexts. That’s why you might feel comfortable farting in front of your family, but not at work. We learn social rules and for the most part try to act in a way that doesn’t jeopardize our social relations.

But trying to actively shame someone for a certain behavior might not generate the result you hope for: common responses to feeling shame can also include getting angry and wanting to distance oneself from the person our group who made you feel ashamed. Or continue with the behavior, but less openly (in Sweden we, anecdotally, for a while started seeing people posting pictures of their train rides…not saying that they were actually taking the train to the airport!).

The thing with shame is that it’s closely tied to social norms, and it usually appears as a consequence of us doing something that is socially unwanted. Which means that it can appear even without actively trying to shame people to not fly, if people perceive that it entails breaking a social norm. And social norms change when enough people start expressing or doing something differently. Like organizing to push for an aviation tax or committing to staying on the ground.

As for feeling flight shame and decide to quit flying, we still know to little to say anything for sure.

Action

If you are a person who still travels by airplane, bear in mind that you belong to a small and privileged minority of the global population, as well as a (globally considered) high emitter. The emissions from your flights will probably make up a large chunk of your overall carbon footprint.

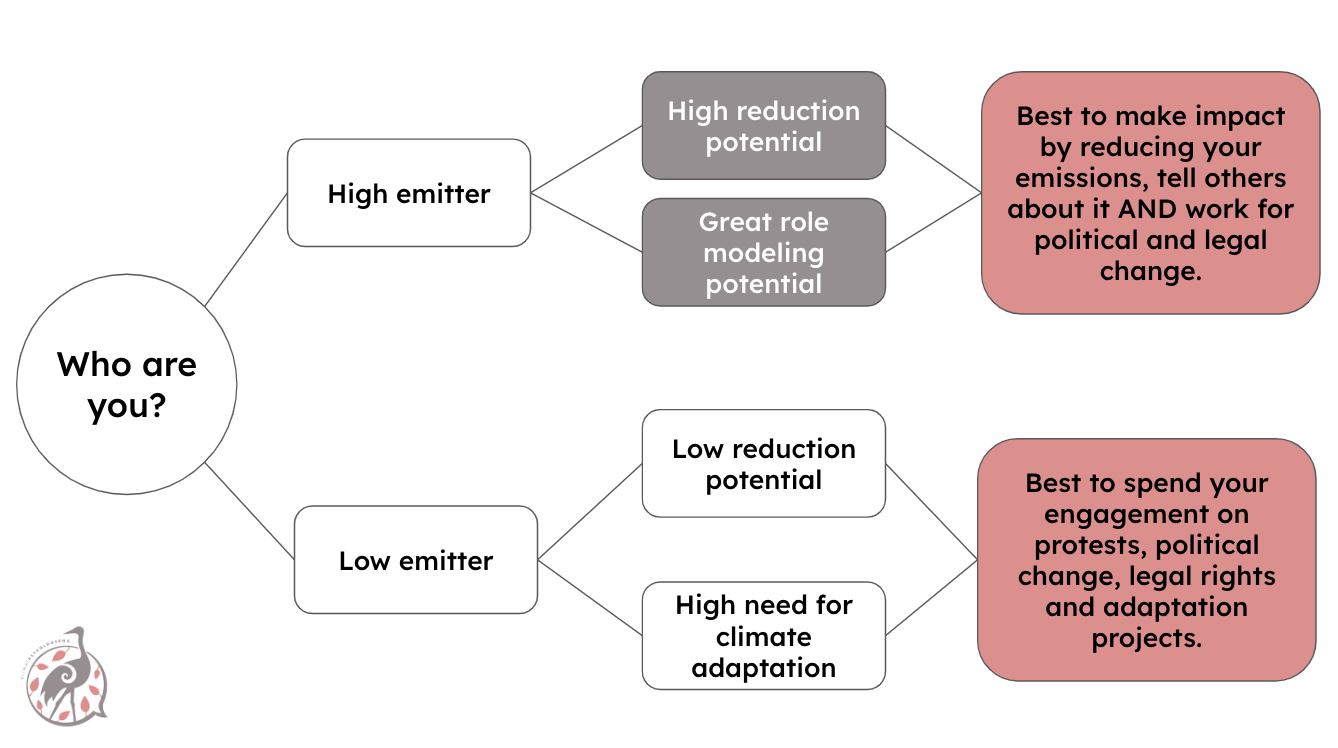

As a high emitter you have a higher emission reduction potential, as well as an important role model potential that can help change social norms. (See the model below, that we’ve also written about here)

Making the change to refrain from flying is also a way of adapting to a sustainable way of living, experiencing firsthand what that can be like. Not flying does not equal not traveling or enjoying life, and it’s quite an amazing thing to be able to experience that.

Remember that we need to do both: individual changes, at the same time as we push for structural change that (in this case) provides cheap, accessible and safe ways of traveling on the ground (or sea).

Trust that fear of shame is potent enough that we don’t need to actively shame anyone into changing their behavior. And that actively shaming someone risks backfiring by triggering anger and distancing, or continuing the behavior in secret.

Thank you for reading! As always, drop a comment or a like, to help us know which posts you appreciate, what you would like to see more (or less) of here. And feel free to share this post with anyone who might be interested.

See you next time!

I really appreciate you writing on this topic which I feel is so often ignored. It is one of those things which seems to be put in the 'too hard basket', as stopping flying is seen as a step too far for some people to take.

I can't speak for other countries but here in Australia international travel is seen as a right. The gap year travelling around the world, the lengthy trips through Europe, they are all viewed as a 'right of passage' for our younger generation and then again on retirement. The size of our country and the distance between cities means people regularly fly for weekends, business trips or interstate holidays multiple times a year. The travel industry is huge and advertising is everywhere.

On a personal level I find it hard to talk to people about this as I don't want to sound 'preachy' or for people to take it as a personal criticism. One example of telling someone why I choose not to fly results in the common response, "but we have to see the world". And, I think this is the challenge we are dealing with. We need to change our values. We need to understand the dire climate situation we are facing. We need to acknowledge that our perceived 'rights' only exist because of our privilege. We need to accept that this obsession with 'seeing the world', overseas holidays and travel is only very recent. For 99.9% of human history we were able to live quite happily while limiting travel to wherever we could reach by foot, horse, car, boat, train etc.

It's a really fascinating topic in relation to psychology - the power of advertising and the ability of the human mind to justify decisions which we feel benefit us.

Thank you!

Thank you for writing about flying. It has been a problematic area for me so it is helpful to read your observations, research and comments. I feel like you outlined in your opening statement. I don't fly but have many friends who do and that is often accompanied to going to a resort somewhere for a holiday in some 3rd world country. They are also people who have the financial means to do what they want. I don't have the courage to challenge these friends. Some of them also travel to visit a relative which to me is a different category, which is hard to reconcile as well. I read the notes below and agree with them - more conversation please. !