There's no one best thing we can do for climate.

Why climate action cannot be a one best, one time thing, but a life long endeavor.

Welcome back to Climate Psyched, the newsletter where we explore all things psychological, behavioral and emotional related to the climate and ecosystem crises.

A few days ago I was struck with an intense wave of climate anxiety. A very distinct consequence of having listened to an interview with one of my favorite Swedish podcasters, who for years has been covering the climate issue with both sharpness and humor. Until he sort of just stopped, which - he explains in the interview - has to do with him realizing that the climate crisis, although “a very serious issue”, isn’t as bad as he previously thought, and that he got tired of the doomer narrative he’d been over consuming for a few years. So no more climate for him. And a feeling of abandonment for me.

Going from indulging doom-and-gloom-takes, then getting overwhelmed/tired/intense climate anxiety, and instead tipping over to what in all frankness is best described as climate delaying discourse, is in no way a unique progression. It is, however, a representation of how the climate crisis too often is perceived as a discursive issue, rather than a real problem with real consequences for real people. If the narrative or framing of the climate crisis becomes more important than the very real consequences of it, it also becomes easier to dismiss the whole issue once you get tired or fed up with it. It also allows for the one doing the dismissing to blame their own inaction on the inability of those engaged in, researching or writing about the climate crisis to frame the issue in an interesting or accessible enough way.

The climate crisis is a very real issue with real consequences. But how we frame it matters for our perception of what actions are necessary and possible to take to mitigate and adapt to it.

But is there a way of moving beyond being dependent on a good enough framing, to a more sustainable long-term engagement with the issue?

Situation

Before the recent election to the European parliament, The Guardian published an article where they’d asked hundreds of climate scientists about the most important thing someone can do for climate. 76% backed voting for politicians who pledge strong climate measures, where fair elections take place.

Articles like this, that seek to answer the question about what the ONE best thing, or TOP 5 things, to do for climate have for years been published on a regular basis. In the research literature there are several studies with a similar aim, most well-known is perhaps the 2017 study from Wynes and Nicholas, that lists what personal actions have the highest impact on direct, individual emission reduction.

While it’s good to educate people about the large difference in impacts between different types of action - the framing of there even being a ONE best thing to do for climate also risks leading to the perception that the climate issue is something we can take on easily and then be done with. “I’ve bought my electric car and put up solar panels, so I’ve done my part” or “I voted for a green candidate, so I’ve fulfilled my democratic duty”.

In the recent election to the European parliament, across several European countries, not the least in Germany and France, far-right parties grew while green parties lost a substantial number of seats. What this will mean for future climate politics in the parliament is yet to be decided, not the least by with whom the moderate members of parliament decide to collaborate. If voting is the most important action an individual can take for climate, does that mean that we should just sit back and watch things unfold until the next election, regardless of how much influence the far-right MP’s get over different issues, including climate politics? Few would agree to that. So how do we move beyond the “One and done”-narrative, and why is it important?

Explanation

How we approach the climate crisis partly depends on the perception of what causes it. Is climate just about emissions in the atmosphere or is the climate crisis ingrained in other societal issues and shaped by how our societies and economies are built? What brought us here in the first place? If we view the emissions as the main problem with the climate crisis, then things would be fixed when (if) emissions decrease to zero. But if the emissions are perceived as a symptom of a faulty system, then the problem isn’t fixed by merely reducing them.

The IPCC reports clearly state that the climate crisis has progressed to a point where it’s no longer possible to only focus on mitigation, but also necessary to adapt to the inevitable consequences of the crisis. Related to adaptation is a much needed focus on building resilience to better cope with and bounce back from acute crises and hardships. Preferably, climate action should focus on these tracks parallell. Luckily, it seems that adaptation and mitigation behavior go quite well together and that the focus on one doesn’t reduce the perceived importance of the other, according to The psychology of climate change adaptation, by Anne van Valkengoed and Linda Steg.

A lot of evidence points towards us not getting fully rid of the crisis in this lifetime, which means that taking climate action, in the wide sense of the word, will be a life long endeavor. But it also means that climate action is more than just climate action; it’s part of an ongoing work to reform our societies into something that is sustainable, nurturing and, in best case, thriving.

What framing works?

There’s quite a bit of research on how different framings of the climate issue affect people’s intention to act and support for climate policies. The results seem to be somewhat mixed, for example that a local framing increases perceptions of problem severity and support for local policy action, that a positive frame, health and environmental frames, and global and immediate frames bolster public support, and that the communicative framing needs to be adapted depending on who the audience or target group is.

Or as this large survey of 60 000 participants across 23 countries found, that “In every country in the study, the “later is too late” narrative outperformed messages focused on economic opportunity, fighting injustice, improving health, or even preventing extreme weather. “

Framing matters, not because the climate issue is a discursive issue, but because words and communication influence action taking. But framing, as it seems, doesn’t have a one-size-fits-all.

Different actions for different people

Regardless of communicative framings, not everyone on this planet can or should do the exact same thing to tackle the climate crisis. This is not to say that people who have the possibility of voting shouldn’t (I think everyone who can should, it’s a democratic honor to be able to!), but a super complex problem, as the climate crisis is, requires not only a multitude of actions, but also that different people engage in different types of behaviors, depending on who they are, and what power and competencies they possess.

Whilst voting in a democratic system means that each eligible voter has the same power as everyone else, what happens in between elections is dependent on how people choose to organize to practice political influence, use their networks (and their money) and be role models by leading the way with their own actions.

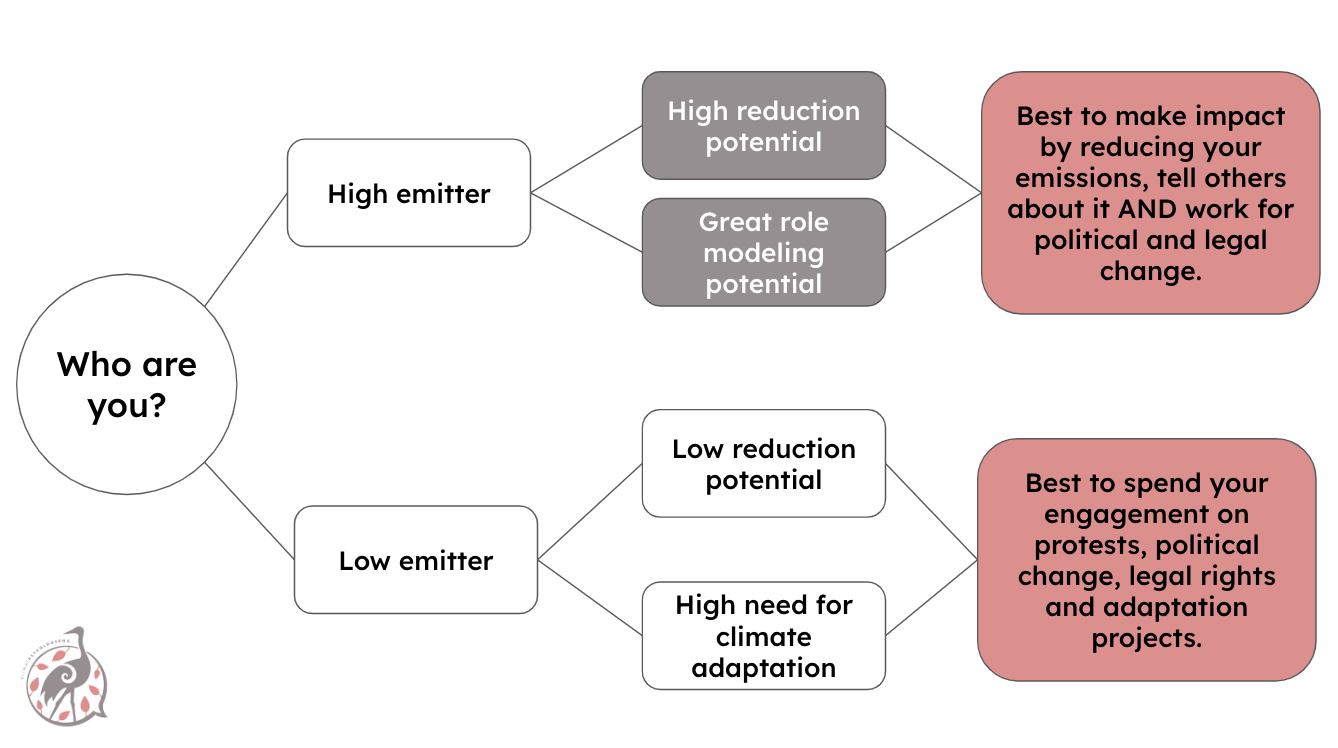

We sometimes use this (very simplified) graph to help visualize that in the ongoing action taking we’re all participating in, the starting point needs to be to reflect on who we are and how we best can contribute. Note that neither of these categories can be reduced to one isolated action, but rather encourages ongoing collective action.

The risk of negative spillover

One thing to remember about human behavior is that our actions are never taken in isolation or from a fully clean slate. What we do will be influenced by what we carry in our backpacks of previous actions, the material and social context in which we live, and the expectations about what our actions will lead to.

This means that one climate action might influence the next, both in a good and bad way: called the spillover effect. Positive spillover is when one action leads to another action, e.g. when voting leads to (i.e. spills over) engaging in a political party, or when recycling leads to taking the train instead of airplane on your vacation. Positive spillover is generally good, but unfortunately it doesn’t seem to happen all that often, especially not automatically.

A less desirable spillover effect is the negative spillover: when one climate action leads to the reduction of another climate action, or leads to the increase of a non-friendly climate action. E.g. when recycling leads to an increase of air travel, or when voting leads to a larger passivity in local engagement. This is sometimes due to moral licensing, when we use one moral behavior to justify another immoral behavior. Other types of negative spillover effects include the rebound effect, Jevon’s paradox and the Negative footprint illusion. The negative spillover effect and how common it is, is still not fully explored in the research literature. But it is a phenomenon that can be observed in various domains, and highlights a potential risk with the “do this one best thing for climate”-narrative.

Making climate action part of your life values to make your own framing

Perhaps less explored in the research literature is how people on a more individual level frame the climate issue in relation to their own action taking and long term motivation.

A slightly different, individual, approach, complementing the general climate communication framings, could be inspired by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). In ACT, a fundamental dimension involves exploring what one’s values are. You know, the things that are truly, genuinely important to you. Values differ from for example goals in the sense that values can never be fully achieved or finished. Rather, they formulate the path on which we wish to continue walking, like a compass guiding our daily steps forward. Values relate to ourselves and how we wish to act and be in this world. They don’t always (and sometimes rarely) describe the easiest way forward, but the way forward that’s meaningful even when it gets rough, and help guide us towards actions that we can be proud of and stand behind.

Examples of values can be:

“To be a caring and present parent”

“To be compassionate towards those who suffer”

“To be curious and open-minded”

“To adjust and adapt readily to changing circumstances”

”To uphold justice and fairness”

While non of these values are explicitly climate related, they can all act as a compass and motivator for our daily climate actions. Fighting for climate is definitely in line with being a caring parent, and spending time with your kids growing vegetables is not only a way of nurturing resilience but also a way to be present with them. Walking in line with the value of being compassionate can act as a reminder to integrate a justice perspective in all actions you take, including those that have an impact on the climate crisis.

Identifying our values can help us shift from seeing climate action as something to be ticked of the list (“I put up solar panels, so I’ve done my part”) to viewing it as an integrated part of our daily lives (“As I strive to be a caring parent, it’s natural to be a part of reducing our collective emissions and to teach my kids skills that will be helpful in future crises”). This means that we don’t even necessarily need to view it as “these are the things I do for climate” or “I’ve done my part”, but instead “this is the way I live, and it’s a way that’s sustainable and in line with my values and what needs to be done in this world”.

Living in line with one’s values is far from a “one and done”-thing. It’s a practice that takes patience and courage, that requires ongoing reflection and to time and again commit to taking action that isn’t necessarily easy, but that is right and meaningful. It’s not a substitute to other communication strategies or policies, but it might offer a complement for individuals to find a more long term motivation - and to help counter the narrative that the climate crisis is something we can conquer quickly and then be done with.

Action

Try shifting from “these are the things I do for climate” to “these are the things I do because they are in line with my values and in line with what I think the world needs”.

Remember that there is no one isolated action that is sufficient at this stage of climate crisis, but rather that we need to take many actions, repeatedly over time and collectively with other people.

Reflect on who you are, what power and competencies you possess and take your starting point there. No one of us has the possibility of doing everything, but in the things we do, we can try and find those actions that together with others can help make a long term difference.

Be aware of negative spillover! Both in your own actions and in the actions you see others take.

I really like this switch in perspective from doing it for the climate actions to "this is the way I live, and it’s a way that’s sustainable and in line with my values and what needs to be done in this world”. I think there are many ways we can talk about switching our perspectives such as from the individualistic to the collective perspective. People are focused on the individual pursuit of happiness and so may balk at reducing their emissions. They don't see how a more collective outlook might actually make them happier, more connected, and secure than the individual consumptive "pursuit of happiness" that really doesn't make them happy at all... just lonely and empty.